The Early History of Akō Castle

The Tōdaiji Temple Territory of Ishishionasu-shō

The first appearance of “Akō” as the name of a region was in 747, where there was an entry for “Akō District, 10 chō” in the Daianji Temple Material Records.1 Further, a wooden tablet that had “Harima Province, Akō District” written on it was excavated from the site of Heijō Palace, which was the capital at the time.

Records from this period show that in 753, Hatano Ōi took control of the new rice fields developed by the Ōtomo clan in the Sakoshi township of Akō District. Hatano then attempted to construct a salt levee, but ultimately failed. There are also records that over 30 cho (~297,521m²) of Mt. Habuyama in Sakoshi township was donated to Todaiji Temple.2 Additionally, Saidaiji Temple had a shiokiyama (a mountain used to gather fuel for salt production) within the Akō District in 770.3 In 743, the Law on Permanent Private Ownership of Newly-Opened Fields was enacted. Under this law, development began to turn the area into salt fields under the management of the temples.

It is said that there was a salt field that spanned roughly 50 cho (~495,868m2) in 842. This salt field was known as Ishishionasu-shō and was controlled by Todaiji temple. Records also show the temple owned 60 cho (595,041m2) of a mountain, which is believed to have been used in gathering fuel for salt production.

Despite these efforts, there is only one entry for the distribution of Akō salt in arrival records at the Hyōgo Northern Checkpoint (Register of Incoming Ships at Hyōgo Northern Checkpoint) in the much later period of the 15th century. It appears that Akō salt wasn’t widely distributed.5 Records indicate that salt production hadn’t had a smooth growth between ancient times and the middle ages.

Rendering of the Lower Chikusagawa River Area in Ancient Times: A rendering based on a combination of maps, names of cities, towns, and villages, as well as excavation results. The area that would become Akō Castle was still underwater at this time. The area that would be Ishishionasu-shō was labeled as “Akōgawa river” to the east, “Sea” to the south, “Ōyomatsubara” to the west, and “Farmers’ Area and Shionasu Yamazaki” to the north.

Rendering of the Lower Chikusagawa River Area in Ancient Times: A rendering based on a combination of maps, names of cities, towns, and villages, as well as excavation results. The area that would become Akō Castle was still underwater at this time. The area that would be Ishishionasu-shō was labeled as “Akōgawa river” to the east, “Sea” to the south, “Ōyomatsubara” to the west, and “Farmers’ Area and Shionasu Yamazaki” to the north.

Sakoshi Township, Akō-shō

According to the Wamyō Ruijushō, a Japanese dictionary of Chinese characters compiled between 931 and 938 (20-volume edition, Kōzanj Temple edition), the Akō district had the 8 townships of Sakoshi, Yano, Ohara, Tsukuma, Yama, Suse, Takada, and Asuka.6 The field of Ishishionasu-shō, which belonged to Tōdaiji temple, was part of Sakoshi township. At the time, Sakoshi township not only included the current area of Sakoshi, but also the areas currently known as Kariya, Shioya, and Osaki. However, until 1153, the only part referred to as “Akō-shō” was the Tōdaiji territory of Ishishionasu-shō.4 A general estimate of the specific area has been made through the use of ancient texts (see map below). Additional excavation efforts at the Dōyama ruins, which are about a kilometer west, have uncovered structures related to the salt fields from the same time period.7 These structures are believed to be of a Kumishiohama-style salt field, where they would collect kansui, concentrated sea water, and boil it down to produce salt.

Records show that in 1158, Akō-shō became a territory of Iwashimizu Hachimangū shrine in Kyoto. There are no records following that period, leaving details unclear until the modern era. Additionally, an article from 1037 shows that Sakoshi-shō, which was near Akō-shō, became a territory of a regent, and the field continued to be in possession of a regent family. Meanwhile, Akō-shō was primarily a field used for producing salt, rather than a village with dwellings. However, there is no doubt that the growth of salt production led to a population influx. According to Banshū Akōgunshi, written by Fujie Yūyō in 1727, there was a village known as Ka-shō at the foot of Kurotaninagaoyama.8 People traveled down to the Hirano area to operate salt fields, which led to the establishment of Kariya (the area that would later become the castle town).

There are nearly no records of the Chikusagawa River area from the middle ages, and much is unknown about the specifics regarding the control of this region. All that is known is that in 1313, the “Kizu Village Fishing Bank within Sakoshi-shō” belonged to the Terada family, who were stewards of the Yano-shō.9

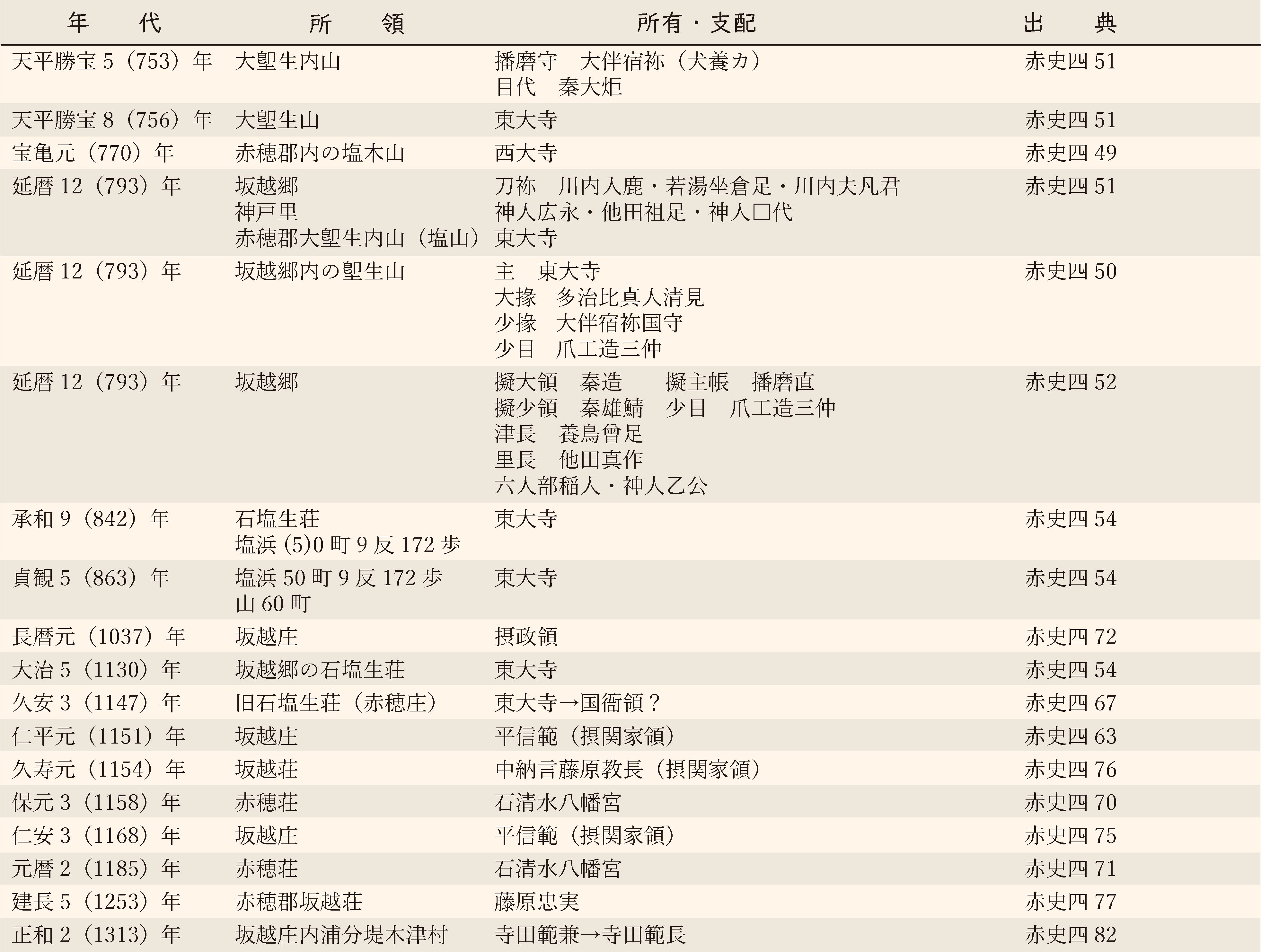

The Ancient Ruling Class of the Lower Chikusagawa River Area: In the sources, “赤史” refers to Akō City History, “4” refers to the fourth volume. The numbers refer to the document number. “一” refers to the relocation of territory.

The Ancient Ruling Class of the Lower Chikusagawa River Area: In the sources, “赤史” refers to Akō City History, “4” refers to the fourth volume. The numbers refer to the document number. “一” refers to the relocation of territory.

The Beginning of the Castle Town

According to Banshu Akōgunshi, the castle of Ōtaka in Higashiuna was relocated here between the years of 1452 and 1454 by Oka Buzennokami Mitsukage (though some sources say Mitsuhiro), a family member of Akamatsu Mitsusuke. This was known as “Kariya Village Old Castle” or “Kariya Old Castle.” This was said to be an area of 7,200 tsubo (~23,802m2) that would later become Icchōme, Teramachi, Okawa, and Yokochō. During this time, there had been multiple migrations from northern foothills, indicating that the development of land had progressed during the 15th century, and it is believed that the area had grown as a base for water transportation and military operations.

Tōshōji temple (later known as Eiōji temple) was built in 1490 in Naka-shō (currently Nakahiro), which is recorded in Register of Incoming Ships at Hyōgo Northern Checkpoint from the 15th century. Additionally, Dairenji temple was built bby 1532, and Manpukuji temple was moved from Naba Ōshima (now Aioi City) to Kariya in 1574. It was during this time that people likely began living in the area. In 1582, Hashiba Hideyoshi ordered the construction of a new embankment in order to attack Bitchū Province. This embankment was expanded later on and became Himeji road, which was the foundation for development of the castle town.

Following that, Tsunami Hōin, a retainer of Ukita Hideie (the lord of the area after Ikoma Chikamasa), established a public office in an area known as Jōgashū. It is said that this was where the residence of Kondō Genpachi later stood in the Sannomaru of Akō Castle. During this time, the base of administrative operations was moved from the Kariya Village Old Castle to the current castle. In 1597, Fumonji temple was built, and Chōanji temple was relocated and rebuilt. By this time, the area had many basic functions that would lead to the castle town we know from the Edo period. However, the roads (in other words, the zoning) that would lead to the townscape we see today wouldn’t appear until the repairs that followed the Great Fire of Kariya, which occurred during the Genna era after Japan entered the Edo period.

- Daianji Temple Material Records. (Daianji temple archives, document no.46)

- Official Documents of Sakoshi and Kobe Townships, Akō District, Harima Province. (Ishizaki Naoya Private Archives)

- Zō Hokkeji Kondō Shogean. (Shōsōin Repository)

- Tōdaiji Temple Fields and Map Catalogue. (Documents of Tōdaiji Temple)

- Hayashiya, Tatsusaburō. Register of Incoming Ships at Hyōgo Northern Checkpoint. Tōshin Bunkō, 1981.

- Wamyō Ruijushō. (Property of Tenri Central Library)

- Hyogo Prefectural Board of Education. Dōyama Ruins. 1995.

- Fujie, Yūyō. Banshū Akōgunshi. 1727. (Akō City History reprint collection, volume 5)

- Uhyōe No Jō Norikane Shoryō Yuzurijō-an. (The Hyakugo Archives)

The Era of the Ikeda Clan

The Rule of the Ikeda Clan

In 1600, Ikeda Terumasa, who was the lord of Himeji Castle, ruled over the 520,000-koku territory of Harima, which included Akō. Akō bordered the eastern province of Bizen, and was a place of strategic importance during a time when the state of affairs was precarious. Terumasa established a defense system for Harima by sending his youngest brother, Nagamasa, to Akō, and building Akō Castle and the castle town.

In 1603, Terumasa’s second son Tadatsugu was given 280,000-koku of Bizen. Nagamasa, who’d been ruling over Akō, was relocated to Shimotsui in Bizen Province (now the Shimotsui area of Kurashiki City, Okayama Prefecture). Akō was then controlled by a local governor.

When Terumasa passed in 1613, his eldest son Toshitaka did not inherit the entirety of the Ikeda territory, and Akō became part of Okayama Domain under the rule of Ikeda Tadatsugu. However, Tadatsugu passed in 1615, and the territory was allocated to his younger brother Masatsuna. It was then that Akō Domain (a 35,000-koku territory) was reestablished. Masatsuna died in 1631, and he had no successor. The territory was given to his younger brother Teruoki, the lord of Hirafuku Domain (now the Hirafuku area of Sayo-cho, Sayo District, Hyogo Prefecture).

As you can see, Akō was a small city that had dizzying changes to its leadership due to various circumstances of the Ikeda clan. Despite all the changes, there was active development in the area, such as the expansion of the castle. This is believed to be a result of the successful development of salt fields.

Salt Field Development

At the time, the Ikeda clan was actively developing salt fields within their territory. There were already traditional Irihama-style salt fields spread across the areas of Himeji and Takasago, which had made them major producers of salt.

In Akō, the river beds were filled through the use of kanna nagashi (a method of efficiently gathering ironsand by pouring massive amounts of dirt into the river and utilizing the difference in density relative to water between materials) in the upper area of Kumamigawa river (now Chikusagawa river). It is believed that frequent floods led to a massive influx of dirt, and tidelands had expanded at the abnormal rate of 5 to 6 meters a year, which provided the optimal environment for developing salt fields.1 A map that depicts the area at the time, Map of Akō Castle Town under Commissioner Ikeda Masatsuna's Domain, shows that there were already many salt fields in the area.

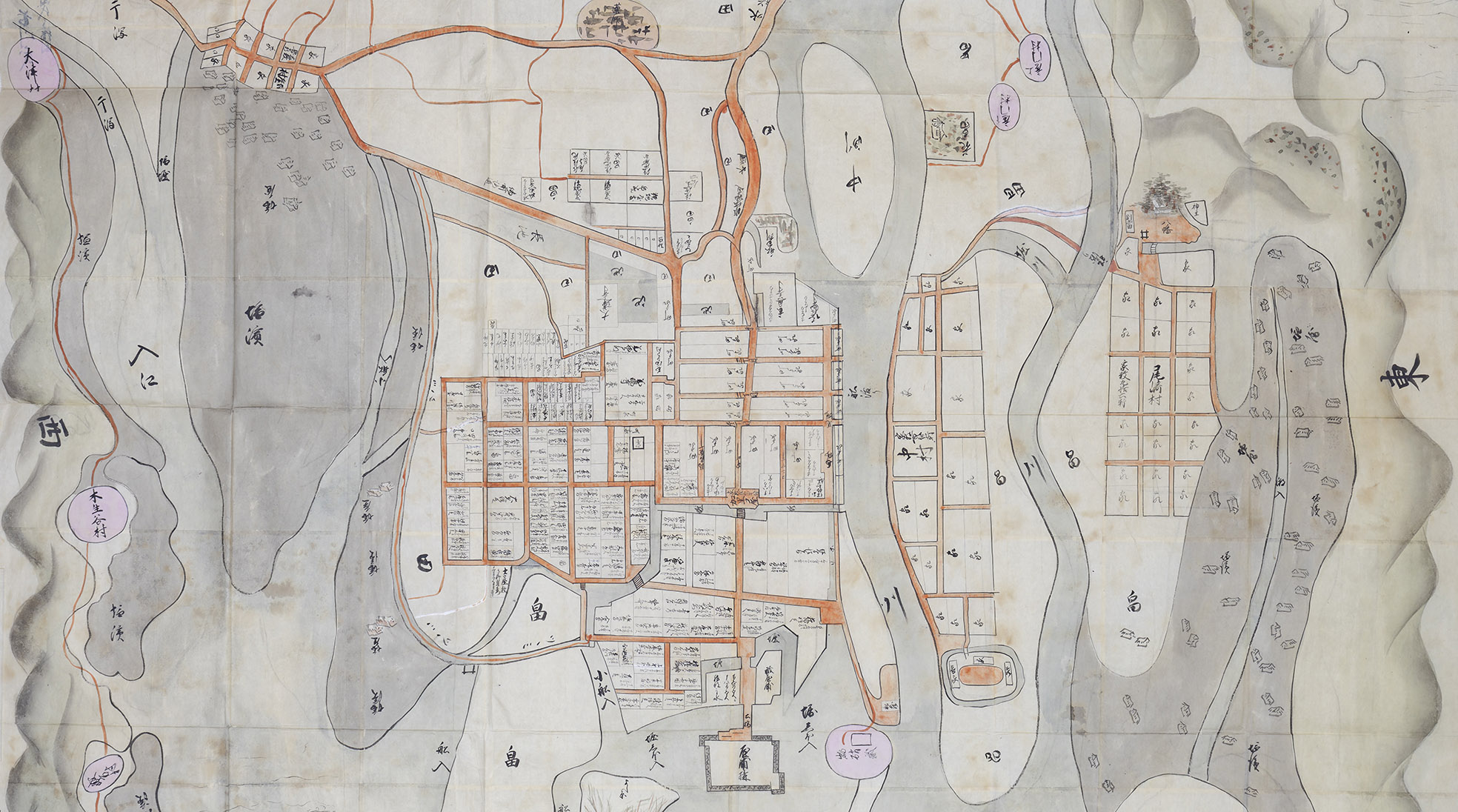

Map of Akō Castle Town under Commissioner Ikeda Masatsuna's Domain. (Property of Maekawa Yoshitsugu): Though this map’s title suggests it was created during Masatsuna’s rule, the inclusion of Myōtenji temple, which was relocated to the area in 1640, suggests that the map depicts the castle town area during the 1640s. The label in the lower-middle area of the map says “Residential Area (Kakiage Castle),” indicating the main subject of the map is the castle town. The salt fields in the area are depicted in gray. The map also shows that Nakasu, the tidal area that had formed south of the castle, was used as farmland.

Map of Akō Castle Town under Commissioner Ikeda Masatsuna's Domain. (Property of Maekawa Yoshitsugu): Though this map’s title suggests it was created during Masatsuna’s rule, the inclusion of Myōtenji temple, which was relocated to the area in 1640, suggests that the map depicts the castle town area during the 1640s. The label in the lower-middle area of the map says “Residential Area (Kakiage Castle),” indicating the main subject of the map is the castle town. The salt fields in the area are depicted in gray. The map also shows that Nakasu, the tidal area that had formed south of the castle, was used as farmland.

Kakiage Castle

When looking at the coast on Map of Akō Castle Town under Commissioner Ikeda Masatsuna's Domain, you can see a castle labeled “residential compound” with rectangular stone walls drawn around it. This is the “single-level Kakiage Castle” recorded in Banshū Akōgunshi, written by Fujie Yūyō in 1727.

This castle was built in 1603 by the local governor of Akō, Tarumi Hanzaemon Katsushige. Inorder to maintain the new castle and a castle town on the land created by Chikusagawa river, Tarumi Katsushige dug the Kiriyama Water tunnel, an aqueduct tunnel, roughly 7 kilometers upstream from Kumamigawa, and utilized the river water for the water supply, creating the Akō waterworks. He then built the castle town, which was connected to Bizen road and Himeji road, and Kakiage Castle, a water castle, in the southern area.

The castle town saw repairs following the Great Fire of Kariya, which occurred during the Genna era, and as an economic strategy, machiya (townhouses that also served as storefronts) were built at the intersection of the northeastern Himeji road and the westbound Bizen road. A samurai residence was placed to the west to defend Kakiage Castle, and an embankment was built further west of the residence as a boundary for the salt fields.

Kakiage Castle, labeled as a residential compound on the map, stood on land that had been created from the dirt brought over by Kumamigawa river. A portion of this land was untouched to leave several inlets for small boats. This was a clever defensive use of the natural terrain. Further, according to Banshū Akōgunshi, the castle had a moat, stone walls, a yagura (tower), fences, and gates, as well as the two-story north-facing Kuromon gate, which served as the front entrance. Additionally, Ikeda Masatsuna built a parlor room, an entryway, a shikidai entryway step, and a dozō storehouse for the lord’s residence on the castle grounds. Teruoki, his successor, built a gold-accented room, several gates, a sumi-yagura (corner turret), and a stable, indicating that by the mid-17th century Kakiage Castle was on its way to becoming a proper castle.

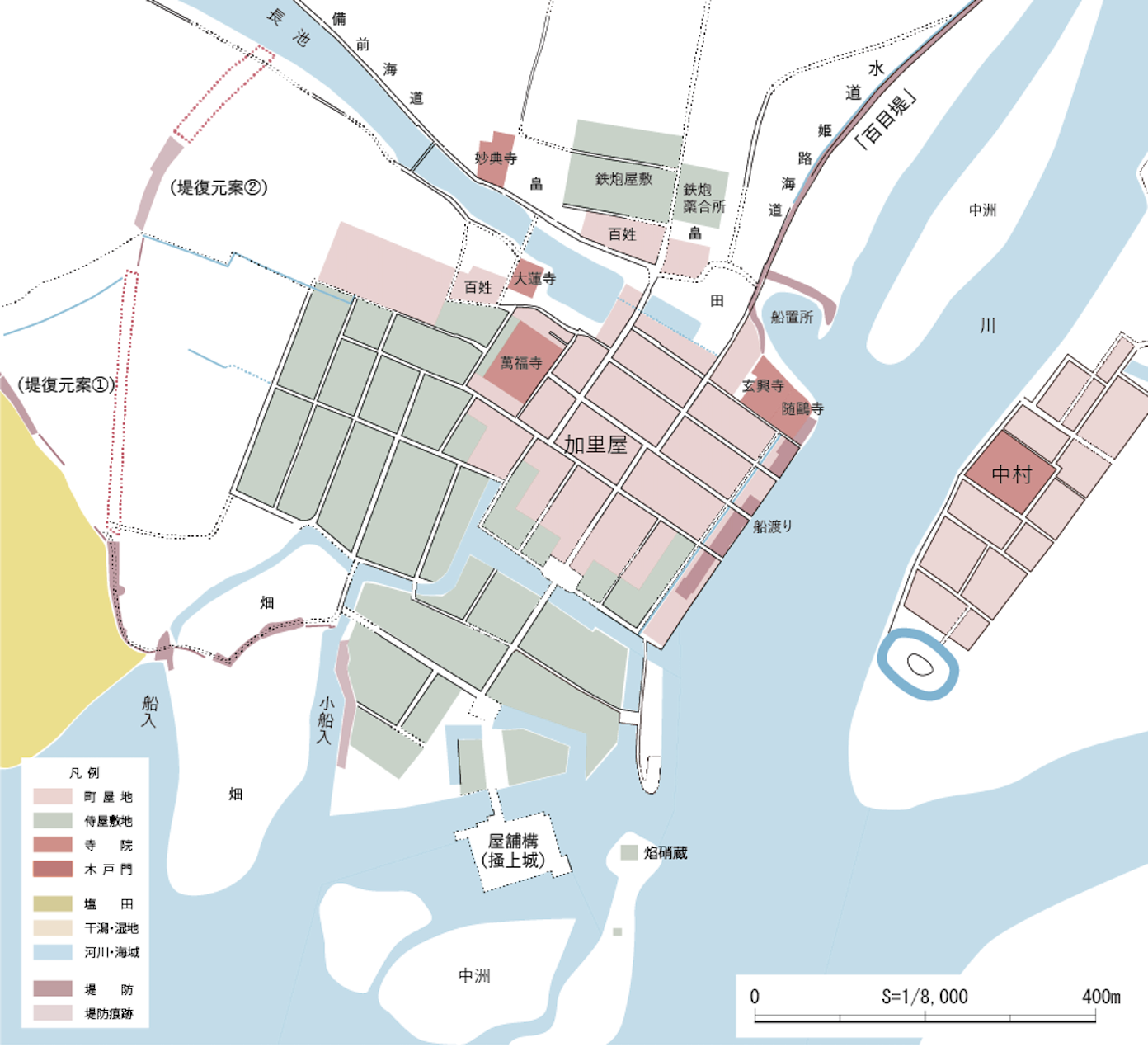

Restored Map of the Ikeda Era Castle Town: A restoration based on resources such as the current layout of roads and a map from the same era.

Restored Map of the Ikeda Era Castle Town: A restoration based on resources such as the current layout of roads and a map from the same era.

The Rule of the Asano Clan

Though the rule of the Ikeda clan appeared to have no issues, Lord Teruoki went mad and received the punishment of kaieki, which included a punitive change in rule. This was the unexpected end of the Ikeda clan’s rule.

In Tokugawa jikki, it is said that Ikeda Teruoki “suddenly went mad and slew his wife (daughter of Provincial Governor of Chikuzen Kuroda Nagamasa), wounded his concubine, and killed both his handmaidens,” on March 15, 1645. Teruoki was dispossessed, and in June of the same year, Asano Naganao, the lord of Kasama Domain in Hitachi Province, was hastily relocated to rule over Akō. Because the Asano clan had been “waiting for a castle” while in Kasama Domain, ruling over Akō provided the opportunity to construct Akō Castle.

- Tanaka, Shingo. “The Natural Environment of Akō.” Akō City History Vol. 1. 1981.

The Construction of Akō Castle

Building Akō Castle

In the Laws for the Military Houses established in 1615, it was stated that “Castles may be repaired, but such activity must be reported to the shogunate. Structural innovations and expansions are forbidden without shogunate permission.” In other words, building a new castle should have been impossible.

However, the Asano clan was related to the Tokugawa clan through marriage, thus changing the minds of the shogunate. The letter from the shogunate ordering the Asano clan’s relocation stated that Akō was a good location, that they were allowed to build a new castle because there was only a residential compound, and that they would be close to the Main Lineage in Hiroshima, among other things (Biography of Lord Kyūgaku).

Asano Naganao immediately began scouting locations to build the castle. In the beginning, the triple mesa of Shioya Kōjinyama was a candidate, however they decided to build on flat terrain (Articles of Lord Asano Naganao’s Affairs, property of Kagakuji Temple). This was perhaps because he had prioritized economic potential over military use.

It is said that Akō Castle began construction in 1648, however this was the year that the shogunate had approved construction. In reality, some work had begun in 1646, the year following Asano control of Akō. This work included mining operations to collect stone for the stone walls, as well as digging operations to create the outer-moat of the Sannomaru in order to make the samurai residences part of the castle grounds (Annual Memorandum of Samurai Residences and Other Various Necessities, property of Kagakuji Temple; Akō City History. Reprint Vol. 5.)

Further, the Ikeda clan’s kokudaka, or production yield, increased from 35,000-koku to 53,500-koku, which was followed by an increase in members of the kashindan (group of samurai retainers). This encouraged the active expansion of samurai residences, as well as machiya townhouses. At the time, Akō displayed great economic prosperity.

In 1648, the shogunate granted permission to construct the castle, and a building site was selected. The following year, they began preparing the land for construction. The rebellion of Yui Shōsetsu caused public unrest, which made it necessary to regain permission to continue construction in 1651. However, it is believed that they were filling in the grounds for the Honmaru and Ninomaru, as they had already designated a borrowing-pit to the west of the castle. In 1652, machiya were removed from the area that would become the Sannomaru entrance.

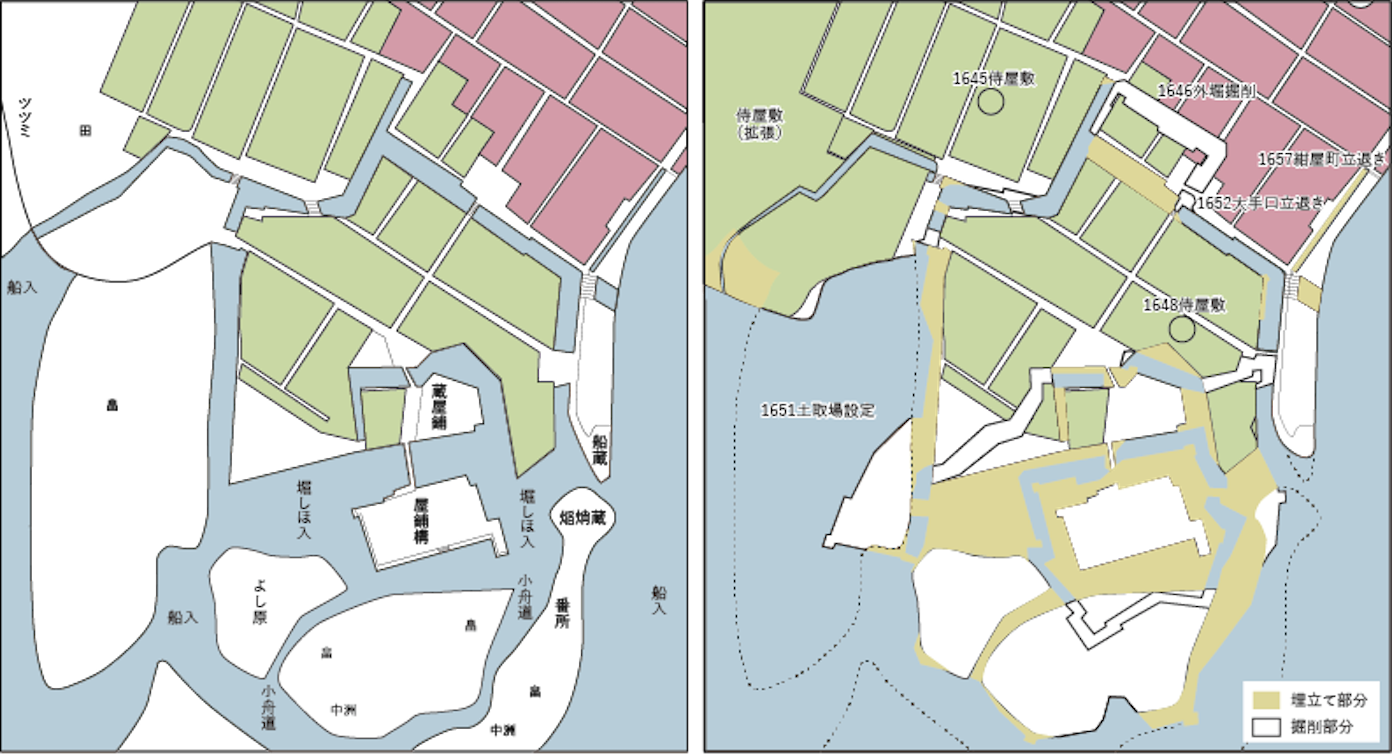

The castle area during the Ikeda era (left) and the estimated area to be filled in for the construction of Akō Castle (right): The map on the left is a reconstruction of the area during the rule of the Ikeda clan. The map on the right is an estimation of how the area in the left map would need to be filled in to match the current terrain, based on the current area of Akō Castle. The items with years listed were determined using entries in Annual Memorandum of Samurai Residences and Other Various Necessities. Areas that needed to be newly filled-in were mainly around the Honmaru and the Ninomaru, indicating that they cleverly utilized the former terrain in designating the castle property.

The castle area during the Ikeda era (left) and the estimated area to be filled in for the construction of Akō Castle (right): The map on the left is a reconstruction of the area during the rule of the Ikeda clan. The map on the right is an estimation of how the area in the left map would need to be filled in to match the current terrain, based on the current area of Akō Castle. The items with years listed were determined using entries in Annual Memorandum of Samurai Residences and Other Various Necessities. Areas that needed to be newly filled-in were mainly around the Honmaru and the Ninomaru, indicating that they cleverly utilized the former terrain in designating the castle property.

And so, construction of Akō Castle was completed in 1661. While it is possible that other parts of the castle, such as the Honmaru and Ninomaru Gardens, were built later on, entries in Annual Memorandum of Samurai Residences and Other Various Necessitiesō indicate that rezoning was completed in 1653, and the expansion of samurai residences was completed in 1658. Because of this, it is fair to say that Naganao’s construction projects were completed when Akō Castle was finished.

A tenshu tower base was built at Akō Castle, but the actual tower was neer built. There are several theories as to why this had happened, but it is believed to be related to the payment of 22,787-koku of rice, 2,477-kan of silver, and 342-ryō of gold for the reconstruction of the Kyoto Inner Palace, as well as the fact that Kondō Masazumi, the architect of Akō Castle, died in 1662.

The story continues a bit later in 1672, a year after Naganao retired. We can see that Nagatomo, the second lord of Akō, was struggling financially, as he stated, “I will release many of my retainers, as I am poor in property.” (Sokōkai. “Clause of 1672.” Yamaga Sokō Sensei Nikki. 1934.)

Map of the Akō Castle Area: The development of salt fields indicates that this map likely depicts the castle town area of Akō Castle post-construction, between the years 1661 and 1669. There are labels for existing and new salt fields, which shows the development of salt fields was expanding at the time.

Map of the Akō Castle Area: The development of salt fields indicates that this map likely depicts the castle town area of Akō Castle post-construction, between the years 1661 and 1669. There are labels for existing and new salt fields, which shows the development of salt fields was expanding at the time.